Tics In Childhood

Tics are sudden, rapid motor manifestations that result from the involuntary contraction of one or more muscle groups. They are involuntary, stereotyped, recurring, unpredictable, non-rhythmic, and temporarily controlled by the will. Tics in childhood are exacerbated by stress or anger and can be mitigated by distraction or concentration.

Tics in childhood are the most common movement disorder in pediatrics. The premonitory urge appears to be the involuntary part of a tic, and the movement is often done to relieve the urge, but younger children with rapid tics describe them as sudden without much warning or voluntary participation.

Tics in childhood: age of onset and course

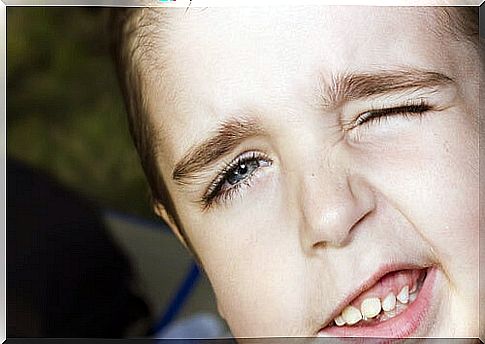

Tics usually begin between the ages of 4 and 7. For most children, the first tics are in the form of repetitive blinking, sniffing, throat clearing, or coughing. They are more common in men than in women, with a ratio of 3 to 1.

Tics fluctuate considerably in severity and frequency. Many children with minor and transient tics between the ages of 4-6 will not seek medical attention. In about 55% – 60% of young people, tics will be minimal in late adolescence or early adulthood.

In another 20-25%, the tics become infrequent but occasional. In about 20%, the tics continue into adulthood (some of which will report a worsening of the tics).

Clinical characteristics of tics

There are certain characteristics that define these motor manifestations. They are as follows:

- Tics are made worse by anxiety, tiredness, illness, excitement, and excessive screen time.

- Tics tend to decrease when a child engages in a cognitively demanding and interesting task.

- Exercise will reduce tics, especially during the duration of physical activity.

- The tics will not interfere with important actions or lead to falls or injury, and any presentation of these tics (also called blocking tics) should alert a clinician to the possibility of a functional component.

- Noticeable differences can be seen when filmed.

- They usually accompany personality disorders, as well as in dysfunctional families.

- They can be accompanied by a certain sensation of pleasure that is expressed facially, despite how complex the movements can be.

- They feel like they can’t suppress them

- They do not present a premonitory sensation.

Classification of tics

Tics are classified into motor or vocal and simple or complex. Simple tics are manifested by sudden movements or short, repetitive sounds. Complex motor tics are sequentially but inappropriately coordinated movements. For example, repeated shaking of the head, repeating the gestures of others (echopraxia), or making obscene gestures (copropraxia).

Complex vocal tics are characterized by elaborate sound productions but placed in an inappropriate environment. An example of this would be the repetition of syllables, blocking, the repetition of their words (palilalia), repeating words heard (echolalia) or pronunciation of obscene words (coprolalia).

How tics are classified in the DSM-5

- Tic disorder provisional (temporary) motor or vocal tics or both that have occurred for less than a year.

- Chronic tic disorder : single or multiple motor tics or vocal tics present for more than a year.

- Tourette syndrome ( TS ): multiple motor tics along with vocal tics that last for a year, do not necessarily have to be present simultaneously and follow an increasing pattern.

Comorbidity of tics in childhood

In children with tics, there is a general presence of impulse control difficulties, subtle differences in neuropsychological and motor functioning, as well as a high rate of psychiatric or developmental comorbidities such as ADHD (30% to 60%), compulsions (30 % to 40%), anxiety (25%), disruptive behavior (10% to 30%), mood disturbances (10%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (5 to 8%), autism spectrum disorder (5%), and motor coordination difficulties. Some children also have episodic rabies.

Etiology

Tics have a complex multigenetic etiology and are highly inherited. The concordance between monozygotic twins is 87%.

In the past, tics were considered related to behavior or stress and were often referred to as ‘nervous habits’ or ‘contractions’, it is now known that tics are neurological movements that can be made worse by anxiety but this is not causal.

The underlying mechanisms involve various neural networks in the brain, between the cortex and the basal ganglia (fronto-striatum-thalamus circuits), but also involve other areas of the brain such as the limbic system, the midbrain, and the cerebellum. Abnormalities in interoceptive awareness and central sensorimotor processing have also been described.

Treatment of tics in childhood: behavioral interventions

Behavioral interventions include various techniques, although the specific treatment to be followed with each child will depend on the previous evaluation carried out, the response to the treatment and the incidents that arise during it (Bados, 2002).

Habit reversal therapy (HRT) and exposure and response prevention (ERP) are evidence-based interventions for tics. TRH and ERP will reduce the combined severity and frequency scores (Yale Global Tic Severity Score) from 40% to 50%.

Habit reversal treatment

The habit reversal treatment proposed by Azrin (Azrin & Peterson, 1988) involves teaching the patient to recognize the premonitory impulse and then teaching them to take an action called a competitive response that reduces the chances of their annoying tic occurring.

It includes 11 main techniques organized in five phases:

- Awareness. Including noticing the stimuli and situations that precede the manifestation of tic.

- The detailed description of the tic and the training in doing it voluntarily.

- Self-observation training to detect tic when it occurs.

- Early detection, training to detect the sensations that precede the performance of the tic.

- Detection of the dangerous situations in which the tic is most likely to trigger.

- Relaxation training.

- Training in making a response incompatible with tic. It is a behavior that must have the following characteristics:

- Prevent the specific behavior of the tic.

- That it is possible to hold it for several minutes

- Produce an increase in awareness of the behavior of which the tic consists.

- Be socially acceptable.

- Be compatible with normal activity.

- It should strengthen the antagonistic muscles of those involved in tic behavior.

- For tics, it usually consists of isometrically tensing the muscles that oppose the movement of the tic.

- Motivation. This phase is aimed at both the patient and the family. It includes three standard motivation techniques:

- Review of the inconvenience of tic.

- Social support. It includes having a person from your environment get involved and help you carry out the procedure.

- Carrying out the behaviors in public. So that the patient experiences that he can perform the proposed method in public.

- Training in generalization. It includes the performance of exercises in which the patient has to imagine performing the exercise in dangerous situations identified in phase 1.

Exposure therapy with response prevention

Exposure and response prevention practice leads to the need for habituation and therapy encourages the patient to feel and tolerate the need for tic (exposure) without doing the tic (prevention of response). In a fixed-duration session, the patient is asked to sustain his tics and a therapist records how long he can do so.

No competition answers or props are used. Patients have multiple assists in each session and the duration of time during which they are able to maintain the tics progressively lengthens.

Doing Exposure with Response Prevention on a regular and systematic basis provides the practice of tolerating tic impulses and, over time, the patient’s ability to control the tics improves. During the session, the therapist refers to the impulses to ask the patient how strong they are, the suggestion in this action exposes the patient to the anguish of having a tic despite talking about it.

Pharmacological treatment of tics in childhood

The decision to use them depends on the nature of the tics and is generally reserved for severe and annoying tics that cause pain or injury. Current evidence marks clonidine (a presynaptic alpha-2 agonist) as the first-line drug.

In contrast, antipsychotics / antidopaminergics appear to be more effective in adults. Clinical practice supports good efficacy for aripiprazole in children.

Benzodiazepines are not regularly used in the treatment of tics, but in an acute and severe clinical situation they are often used. They can be used as a way to reduce anxiety in tic attacks but it is preferred to avoid them as there may be a rebound effect.