Drugs Really Hurt When We Can’t See Another Way Out

The consumption and addiction to certain substances have been tried to explain from different perspectives and perhaps all of them have some reason. One of the most explored is the one that encompasses the environmental factors that have been identified in different investigations as risk factors associated with the consumption and addiction to a certain drug.

On the other hand, trying to isolate the addictive component of a drug without taking into account the circumstances and particular characteristics of the person who uses it is a mistake. Really, if we want to understand the problem, we are obliged to go beyond the substance itself, with its addictive power and not forget the consumer, each consumer.

In this way we can answer a simple question, which in turn exemplifies the idea we want to present. For example, why are there people who consume alcohol, even who consume it with certain frequency and not in low amounts and do not fall into addiction?

The rats that only had drugs and those that had slides

We can try to analyze the phenomenon of addiction by looking into the laboratory. In the first experiment, a rat is found in a cage with two bottles of water. One with just water and the other with diluted heroin or cocaine.

Almost every time the experiment was repeated, the rat became obsessed with drugged water and kept coming back for more until it died. This could be explained by the action of the drug in the brain. However, in the 1970s, a Vancouver psychology professor, Bruce Alexander, revised and redesigned the experiment.

This psychologist built a rat park (Rat Park). It was a cage of fun in which the rats had colored balls, tunnels to run around, lots of friends and food in abundance; in short, everything a rat could wish for. In the rat park, everyone tried the two water cans because they did not know what they contained.

What happened is that the rats that had a good life did not become “prisoners” of the drug. In general, they avoided drinking it and used less than a quarter of the drugs that isolated rats took. None died. While the rats that were lonely and unhappy and became addicted fared worse.

The design of the first experiment did not take into account that the rat could only be prowling the box following reflexes and basic stimuli or limit itself to drinking the water with the drug, something that at least already implied a different motor activity and something to do, with regardless of how attractive the drug might be to her.

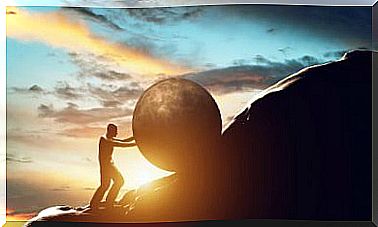

Instead, the second experiment offers them an ALTERNATIVE and not just any: a very attractive, striking and reinforcing activity in itself. The rats that had a good alternative or simply a pleasant routine in their life did not feel the need to continuously drink the water with a substance that stimulated in the center of the pacer; or at least they didn’t notice that imbalance.

It was even more surprising when a third revision of the experiment introduced rats that had spent 57 days confined in cages with the only option to consume drugs. It was observed that once abstinence was over and in a happy environment, all recovered.

The drug is not by itself a powerful enough behavior enhancer if it does not settle into vital clutches orphaned of affection, healthy routines or decent work. Perhaps, once established, it becomes an addictive behavior that is maintained by mere repetition or / and destruction of life itself, but its starting point is much more complex.

An explanation that gives us hope and meaning, far from moralistic or chemically reductionist views that present the addict as someone weak of character. It makes us understand that addicts, saving distances, could be like rats in the first cage: isolated, alone and with only one way of escape or pleasure at their disposal. On the other hand, a person who takes drugs, but returns to a satisfactory environment, can avoid falling into addiction because he has many other stimuli at his disposal that start his brain reward circuit.

In this sense, the key is to build ourselves a “cage” that tastes like freedom. A “cage” in which we have different alternatives that we can exchange to produce pleasant sensations, so that we do not end up generating dependence on any. In this sense, drugs are bad, but they are even worse when they appear in a context of hopelessness in which the person is not able to see any possible alternative to cling to in order to feel good … because we all want to feel good, if only for a few moments.